Companies are pursuing product life cycle assessments (LCAs) for the first time due to new sustainability regulations; the ability to quantify the sustainability of sold goods; and changing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) rater methodologies. Despite sustainability professionals’ unfamiliarity with LCAs, companies increasingly turn to their sustainability departments to execute and publish product LCAs, especially because LCAs can be used for product greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting or product chemical disclosures. As LCA reporting requirements and stakeholder expectations mature, it is critical for sustainability specialists to understand the following concepts, which are detailed below:

- The Importance of LCAs

- LCA Phases

- Regulator & Stakeholder Expectations of LCAs

- Actions to Take Now in Preparing for LCA Reporting

The Importance of LCAs

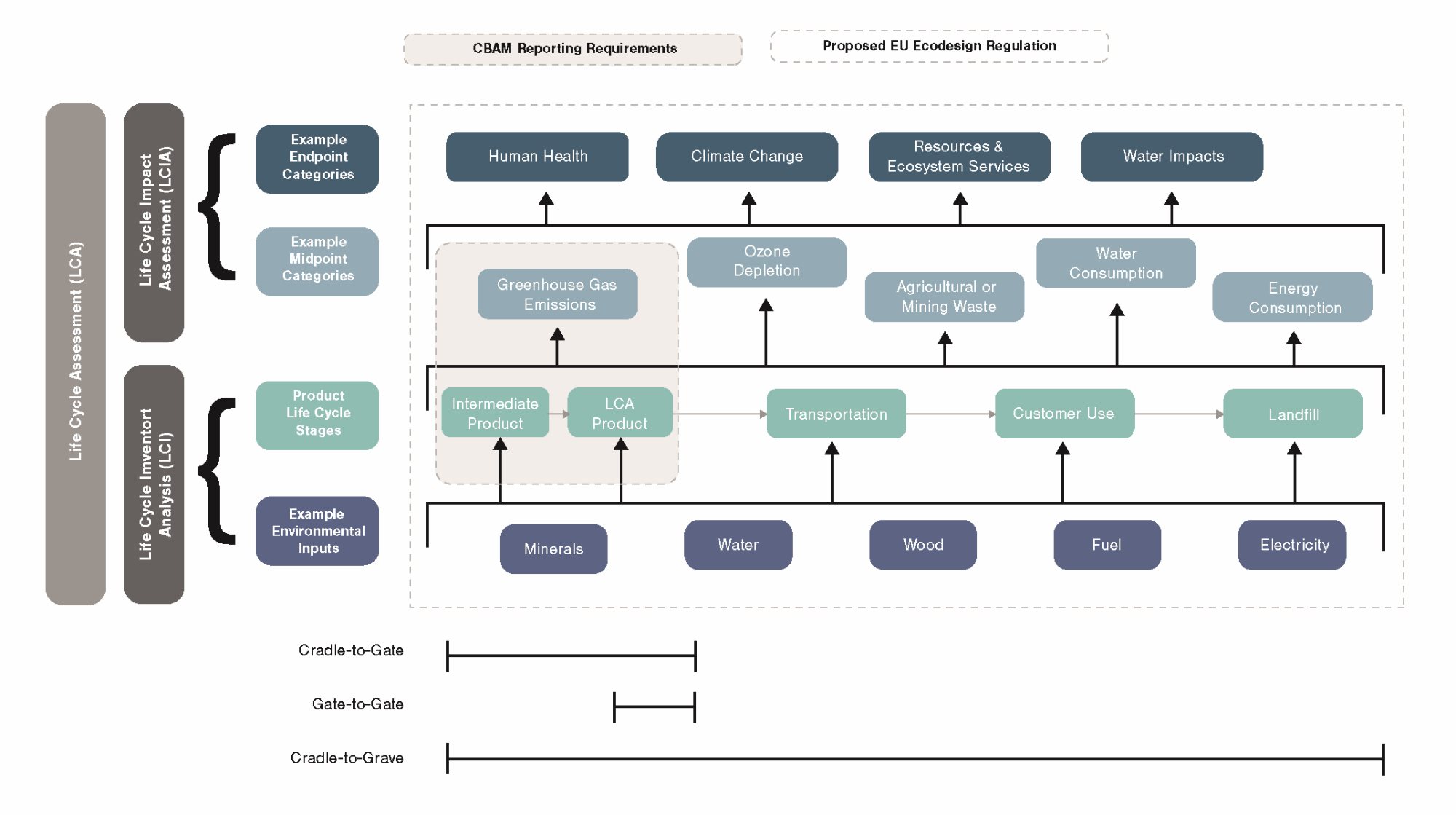

An LCA is a method for assessing the “environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life.” The LCA author analyzes the flow of material to and from a product’s production, incorporates each step of a product’s manufacturing process, determines how the product will be used by the average consumer, and evaluates how the consumer treats the product through the end of its life. By examining the product’s supply chain, manufacturing, use, impacts, and disposal, the LCA author identifies opportunities to reduce the environmental impacts of the product and communicates how the product is made.

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Example Endpoint Categories

- Human Health

- Climate Change

- Resources and Ecosystem Services

- Water Impacts

- Example Midpoint Categories

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- CBAM Reporting Requirements

- Ozone Depletion

- Agricultural or Mining Waste

- Water Consumption

- Energy Consumption

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Example Endpoint Categories

- Life Cycle Inventory Analysis (LCI)

- Product Life Cycle Stages

- Intermediate Product

- CBAM Reporting Requirements

- LCA Product

- CBAM Reporting Requirements

- Transportation

- Customer Use

- Landfill

- Intermediate Product

- Example Environmental Inputs

- Minerals

- Water

- Wood

- Fuel

- Electricity

- Product Life Cycle Stages

- Cradle-to-Gate

- Gate-to-Gate

- Cradle-to-Grave

LCA Phases

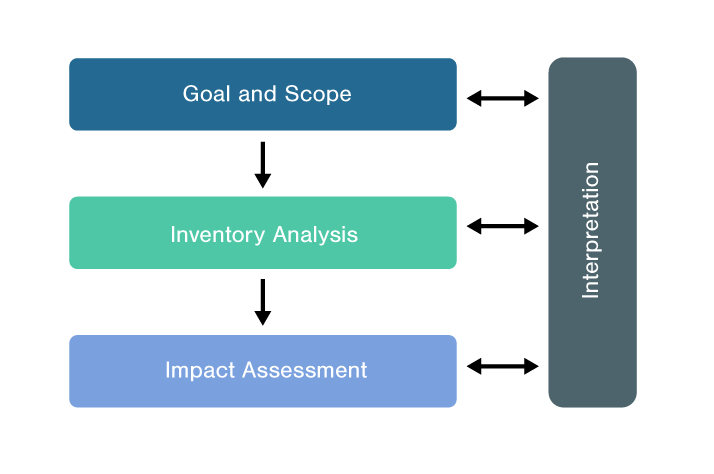

An LCA has four phases: goal and scoping, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation. The interpretation phase occurs simultaneously with the other three phases (Figure 2).

- Interpretation

- Goal and Scope

- Inventory Analysis

- Impact Assessment

In the goal and scoping phase, the LCA author defines what exactly will be studied, such as intended application, regulatory requirements, reason for the study, system boundaries,1 functional unit,2 product system,3 value choices, quality reviews, and reference flows4 (see Figure 1).

During the life cycle inventory analysis (LCI), the author identifies the precise value chain steps. Major energy inputs, raw materials inputs, products, co-products, waste, and environmental releases are diagramed. A key component of the LCI is understanding when and how to allocate flows. For example, consider an LCI of carrots: If carrots and lettuce are grown in the same field, the author should allocate the percentage of field inputs, e.g., fertilizer, water, and pesticides, to growing carrots.

In completing the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), the author selects the environmental impact categories and the endpoints of those impacts. For example, if a company is interested in water pollution from the fertilized carrot field, the author should identify which chemicals were released to the environment through the LCI, e.g., the amount of nitrates. Next, the author should identify the impact category, e.g., aquatic eutrophication, and proceed to quantitatively determine the negative impacts, e.g., increased nitrogen content per liter of water per functional unit. The endpoint would be the degraded aquatic habitat.

Throughout the LCA, the author interprets the results to understand where improvements can be made to reduce environmental impacts or find efficiencies. If data gaps are found, the study author should review the LCA’s definition and scope to determine the necessary steps to fill or describe the data gaps.

Regulator & Stakeholder Expectations of LCAs

European Union eco-design regulations, often referred to as the European Product Registry for Energy Labelling (EPRL), focus on energy-efficiency requirements for large appliances5,6 and assess a product’s energy efficiency, recyclability, ability to reduce environmental impacts, and alignment with specific product-level requirements, which is achieved through conducting an LCA.7 LCAs also will need to be conducted to achieve compliance with the proposed EU Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), which requires the disclosure of certain products’8 durability, energy efficiency, recycled content, carbon footprint, and other characteristics. The proposed ESPR regulations would require LCAs for nearly all physical goods sold in the EU (see Figure 1). Priority product groups would be identified based on their potential contribution to the EU’s climate, energy efficiency, and environmental goals. The EU will consider whether a product could be improved without incurring additional substantial costs and make a recommendation for inclusion in ESPR.9

In some circumstances, companies may need to submit a simplified LCA (SLCA) instead of a full LCA. The regulations that commonly require SLCAs are for product chemical disclosures—such as the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) or the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH)—and examine whether a product generates specific pollutants. Companies that import cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen into the EU are subject to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Companies reporting under CBAM must disclose the GHG emissions generated from antecedent intermediate products, the manufacturing of certain products, and the electricity needed to manufacture the product through an SLCA focused on GHG emissions. These disclosures, along with any carbon price paid on the GHG emissions, are reported when a company imports applicable products into the EU (see Figure 1).

Further, ESG raters have begun assessing whether a company has conducted and published LCAs. If a publicly available LCA is absent, the assessed company’s ESG rating may be negatively impacted. Based on proposed regulations and ESG rater methodologies, manufacturers in the consumer goods sector, e.g., companies manufacturing appliance, semi-conductor, household and building products, and CBAM-applicable importers should be attentive to both stakeholder LCA reporting requirements and emerging regulations in the EU and elsewhere.

Actions to Take Now in Preparing for Product LCA Reporting

Sustainability professionals should start by performing an assessment of the regulatory landscape and their own products’ value chain. Even when an organization is not directly required to provide a product LCA, the sustainability team may still have to author an LCA based on supplier or client demands. As a best practice, sustainability professionals should conduct LCAs in accordance with the methodologies found in the regulations, which may align with ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. Full product LCAs are a complex endeavor requiring months of preparation, data collection, and analysis. If requested to conduct an LCA, the sustainability professional should immediately engage with a cross-functional group of internal and external stakeholders to understand the product’s origins, resource consumption, use, and end-of-life characteristics.

The increased knowledge and understanding of LCAs will encourage organizations to grow in further learning and development of how to manufacture more sustainable products. Measuring the impact organizations have on the environment continues to garner scrutiny, evident through heightened regulatory developments and stronger demands for greater sustainability reporting transparency and accountability, as well as elevated shareholder expectations. With this in mind, sustainability professionals should understand disclosure requirement compliance, be able to conduct product comparisons that lead to market positioning, and continue advancing their organization’s sustainability journey through encouraging more sustainable products.

If you have any questions or need assistance, please reach out to a professional at Forvis Mazars.

- 1Set of criteria specifying which reference flows are part of a product system. Common system boundaries are “cradle-to-grave,” i.e., from resource extraction to the product’s end of life, “cradle-to-gate,” i.e., from resource extraction through final assembly, and “gate-to-gate,” i.e., isolating processes within the company’s manufacturing site.

- 2The service that a product provides.

- 3Collection of flows that models the life cycle of a product.

- 4Amount of goods or services purchased per functional unit.

- 5“The new ecodesign measures explained,” ec.europa.eu.

- 6"Energy-efficient products,” commission.europa.eu.

- 7“Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation,” commission.europa.eu.

- 8The proposed rule will include many physical goods, except for food, feed, medicinal, and veterinary products.

- 9“Ecodesign for sustainable products,” europarl.europa.eu, page 5.